An Ode to Vincent

My lifelong love of horror icon & art patron Vincent Price

The first time I was old enough to tell the barber what kind of haircut I wanted, I asked him to “make me look like Vincent Price.”

I’m sure it was a strange thing to hear from a 7 year old, but to the man’s credit, I left that barbershop 30 minutes later bearing the actor’s signature slicked-back swoop.

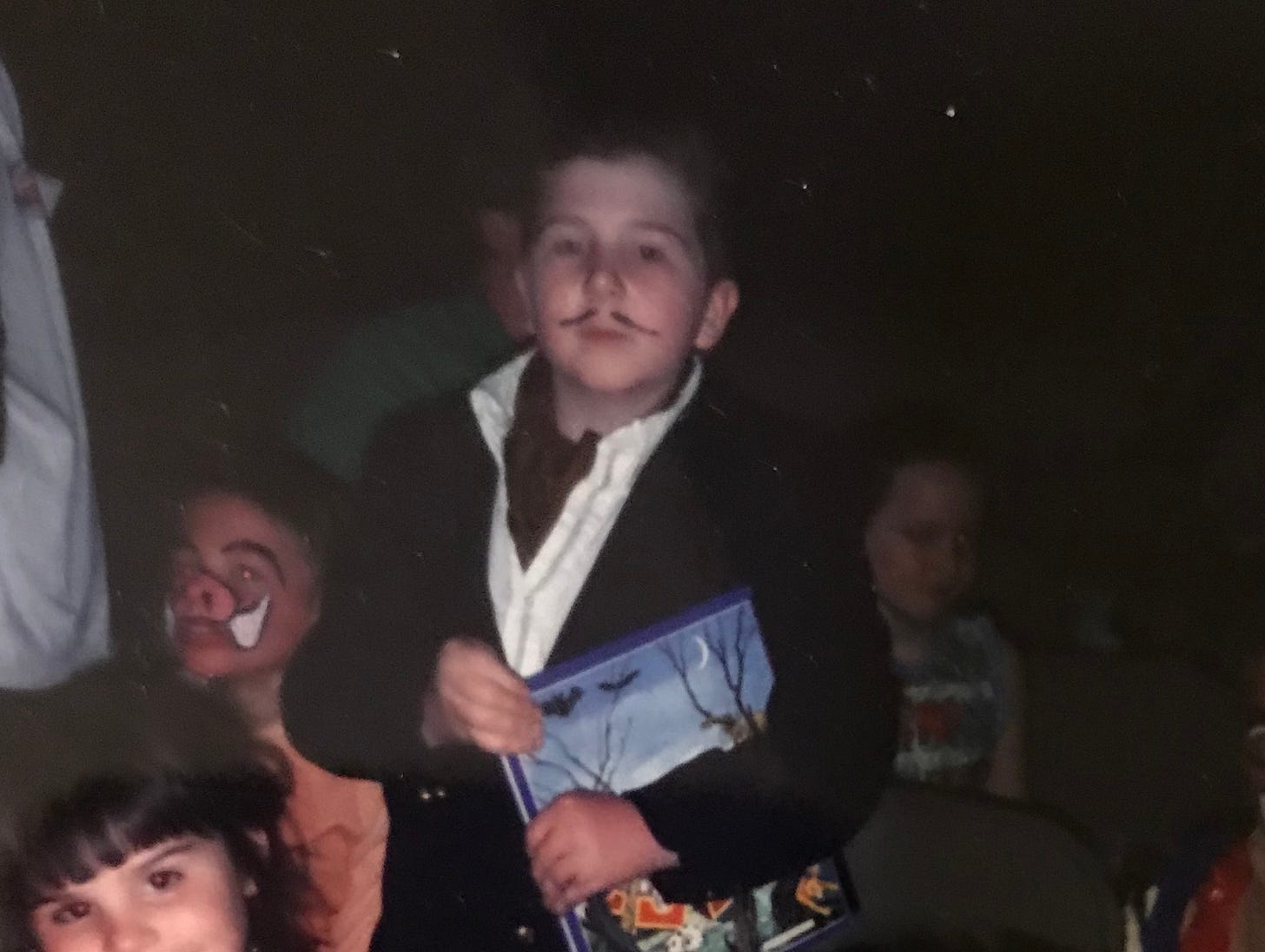

Why did I want to look like Vincent Price? Because I was impersonating him for my Catholic School’s talent show, of course. Here’s some photographic evidence.

My introduction to the filmography of Mr. Price came two years earlier, when my dad brought home a VHS of the 1959 William Castle horror movie The House on Haunted Hill. Its cover depicted a splashy painting of a giant skeleton towering over a dignified, mustached man holding a single candle in one hand, and a severed head in the other. I was immediately enthralled.

We watched it that night, my dad, my brothers and I, in the living room with all the lights off. Before the credits began to roll, the screen went black and a chorus of hysterical screams, clanking chains and maniacal laughter joined together to form a sort of introductory soundscape. Right away, I knew I was in over my head. I remember burying my face in my dad’s shoulder until he said “Look, it’s Vincent Price. He doesn’t seem so scary, does he?”

The face of the man from the VHS cover was now superimposed on our tv, welcoming us to a party at the titular haunted house. And in truth, my dad was right. He didn’t seem that scary. He was a sly, debonair man with a wry smile and a manicured mustache much like Captain Hook’s. I instantly knew he was my people. And that night marked the beginning of my years-long mission to see every last one of his movies.

Before House on Haunted Hill, before The Fly, The Pit & The Pendulum and the Thriller music video, Vincent Price was a St Louis-born heir to the National Candy Company. His grandfather had invented the first “cream of tartar” based baking soda and that afforded the Price family with a fortune befitting the actor’s aristocratic persona.

It’s worth noting that for all his characters’ villainy and crimes against nature, there was always some warmth in Vincent Price’s eyes. Almost like the bleeding heart within him couldn’t help but shine through his pancake makeup.

From a young age, Price was an avid art collector, a passion that would define much of his wide-ranging advocacy outside of his film career. He served under President Eisenhower as a commissioner for the Indian Arts & Crafts board, a role which led to lifelong work in promoting the careers of Indigenous-American artists. To this day, the Vincent Price Museum in East LA, which he founded by donating 2000 pieces of his own collection, is free to the public and historically showcases the work of artists from underrepresented communities.

Public access to fine art was a major cause Price championed, which is why he traveled the country curating 50,000 paintings by famed masters and local artists alike to be sold by Sears & Roebuck in the 1960’s and 70’s. As his daughter Victoria put it, “He saw it as an opportunity to put his populist beliefs into practice, to bring art to the American public."

A progressive voice in Hollywood, and an outspoken “pre-war anti-Nazi,” Price was “gray-listed” in the film industry, after using his radio platform to decry “religious and racial prejudice as a poison” in a 1950 episode of The Saint. He was also an honorary board member of PFLAG, and an early supporter of gay rights.

But as a little kid, I didn’t know any of that. All I knew was he was a different sort of actor than I was used to seeing in black & white movies. He wasn’t a gruff cowboy, or a stiff-lipped, ramrod-straight action star. His power dwelled in the fact that he had presence. The trademark sophistication with which he became synonymous wasn’t stuffy, wimpy or self-serious, as I’d seen depicted in other queer-coded characters of the era. Despite his antagonistic leanings, Price was inarguably a leading man. Intelligent, charismatic and effortlessly self-possessed.

As the youngest of four boys and the lone disabled kid in a family of sports prodigies, I often struggled to imagine how I could possibly contort myself in a way that would make it halfway feasible to follow in their footsteps. But Vincent Price gave me a glimpse into a future I hadn’t even considered. A new definition of manhood that I could actually see myself in.

To be clear, it wasn’t that I was drawn to submerging victims in a vat of boiling wax, or subjecting them to occult rituals and medieval torture devices. But I could see myself being a delightful party host like he was in Masque of the Red Death. Or a wittily self-deprecating sorcerer like he was in The Raven. In fact, amidst his repertoire of murderers, madmen and malefactors, you’d be hard-pressed to find a Price character that you wouldn’t be delighted to find seated next to you at a wedding. And that seemed like a much more desirable livelihood to me than being a police officer or football player.

I sometimes wonder if my dad was knew that when he picked up that VHS of House on Haunted Hill on his way home from work all those years ago. Maybe he’d noticed me drawing undead brides on a legal pad while the rest of the family watched The World Series. Or perhaps he saw in me flashes of his own childhood, spent watching Vincent Price films in the Brooklyn movie houses he grew up frequenting, and figured this might be something we could share. Whatever the reason, introducing House on Haunted Hill to me at such a young age ended up being a deeply meaningful bit of parenting, despite the fact that it features perhaps the most recurring image from my childhood nightmares:

On October 25th, 1993, while sitting at the breakfast table, my parents broke the sad news to me that Vincent Price had passed away. I remember crying as though he was a beloved uncle. I was allowed to stay home from school that day, which at the time I thought was out of respect for my grief, but in retrospect, more likely it was because I was running a fever.

I spent that morning curled up on the couch, watching The Tingler, another Castle schlockfest in which Price plays a scientist who discovers a giant species of parasite that attaches itself to the spines of human hosts and feeds off fear. Regardless of the plot, he plays it with the gravitas and humanity of Lear or MacBeth or Richard the III.

Decades later, shortly after my husband and I moved to Los Angeles, I was sitting on our apartment building’s roof, stewing after a particularly disheartening day. I had just received a spate of script rejections, and narrowly missed out on getting hired by a show I loved. Desperate for some sign I was in the right place, some indication that I should keep at it and not lose hope in the type of man I’d grown up to be, I scanned the Los Feliz landscape. Mountains. Mansions I’d never be able to afford. But then my eyes fell on a familiar structure I hadn’t noticed before in the distance. It was a house. On a hill.

More specifically, it was the Ennis House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, though perhaps most famously known as the titular mansion from The House on Haunted Hill.

If only my 5 year old self could see me now. Living a ghost’s cry away from Vincent’s own fictional abode. I heaved a fortifying sigh and returned to our apartment downstairs where I got back to work.

I still look at Vincent Price as my people. I own his cookbooks. I’ve read his memoir I Like What I Know, which my dad got me a signed copy of for Christmas a few years back. I’ve dressed as him for Halloween, this time utilizing my own mustache.

And while I may not have his style, his taste or his upbringing, I can’t help think that if we were to cross paths at a dinner party or seance, he might think I’m his people too.

An archivist I know processed his papers at Yale and got to talk to him about it. She said he was so wonderful and kind.

This is lovely.